By Jae-Ha Kim

Chicago Sun-Times

February 27, 2003

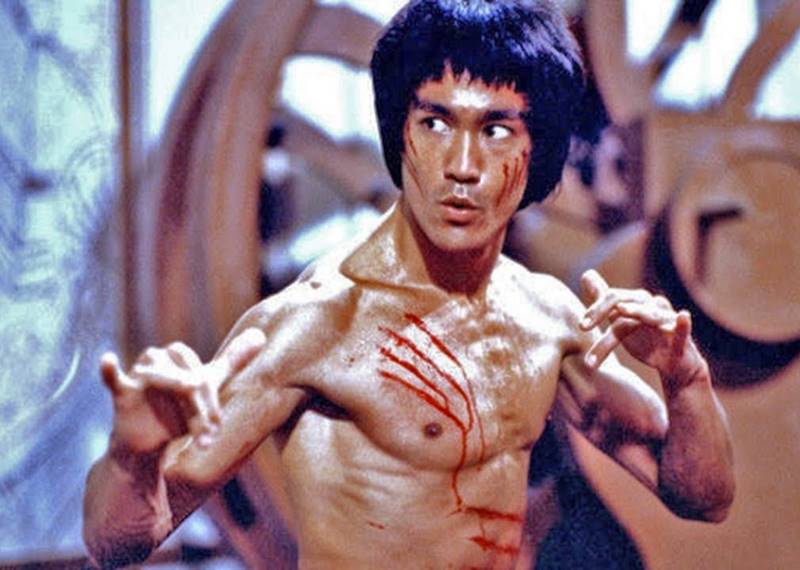

Two decades before Jet Li and DMX joined forces for “Cradle 2 the Grave”–which opens Friday–Bruce Lee was kicking it with Jim Kelly in “Enter the Dragon.”

Back then, pairing an Asian-American martial arts star (Lee was born in the United States and raised in Hong Kong) with a black karate champ-turned-actor was a novelty. These days, it’s good business to keep faith with the audience that first embraced martial arts films in the United States–African Americans.

The “Rush Hour” films–which paired Jackie Chan with motormouth comic Chris Tucker–both opened at No. 1 at the box office. The sequel grossed even more domestically than “The Matrix.”

Without a doubt, Lee–who died of cerebral edema in 1973, shortly before “Enter the Dragon” opened–set the template for the box office hits to come. It was the first U.S.-produced martial arts film.

“‘Enter the Dragon’ is a seminal film that made Bruce Lee a star and introduced the West to these types of films,” says Paul Dergarabedian, president of the box office tracking firm Exhibitor Relations Co. “He had a huge impact on America’s appetite for these ‘chop socky’ action movies. Kids who weren’t even born then know who he is because he was such a charismatic icon. He’s a legend, and the Jackie Chans and Jet Lis of the world learned a lot from him.”

Certainly, the production value of today’s martial arts films are a far cry from the limited budgets of Lee’s pictures. “Game of Death” was his only movie to be made with sound. In his previous films the actors’ voices were dubbed in later, during post-production work.

But the artistry of his lethal, yet graceful moves is something every martial artist-turned-actor has tried to emulate, including Jean-Claude Van Damme and Steven Seagal.

And to inner-city kids, Lee was the underdog who ruled. When he smashed in a sign that stated, “No dogs or Chinese allowed,” in one of his films, they related it to the racism they faced in their own lives. He not only taught martial arts to African-American heroes such as basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, but he also called them his friends. Abdul-Jabbar’s No. 33 jersey number was a tribute to how old Lee would’ve been had he celebrated his birthday that year.

When Harry Lennix was growing up on the South Side, he looked forward to the days when he and his brothers would be treated to a triple feature at their local theater.

“If you were lucky, two of them would be Bruce Lee movies,” says Lennix, now himself an actor who has roles in both sequels to “The Matrix.” “Sometimes there’d be rats running across our feet, but we didn’t care. We were tiny little kids who got to see him do all these amazing things on screen.

“You know how comic books would pit superheroes against each other? We would wonder what would happen if Bruce Lee fought Jim Kelly or Muhammad Ali. The only thing that would’ve made us happier was if we found out that Bruce Lee’s grandfather had been black.”

He wasn’t black, but he also wasn’t white. And that was something to which most minorities could relate.

“When martial arts films first were introduced here, the people who took it seriously and embraced it–even more than Asian Americans–were the blacks and Hispanics,” says former Chicagoan Ho-Sung Pak, a martial arts champion and actor who appeared opposite Jackie Chan in “Legend of Drunken Master.” “The urban audience related to seeing Asians in those movies because we were all minorities. There’s no question in my mind that it was the urban audience that made martial art films acceptable and cool.”

When Jackie Chan was honored at MTV’s annual movie awards during the late 1990s, it was no coincidence that Hong Kong film buff Quentin Tarantino introduced him and the music that accompanied Chan’s walk to the podium was Carl Douglas’ 1974 hit “Kung Fu Fighting.” Never mind that some of the lyrics aren’t politically correct today (“There were funky Chinamen”). The song perfectly captured the urban audience’s fascination with martial arts films.

As with many pairings, the love affair between blacks and kung fu films sprang out of financial necessity. Unlike Chan’s and Li’s big budget feature films today, the majority of Lee’s films were made with little backing. His films didn’t play at the marquee cinemas either. Rather, they were staples at inner-city theaters.

In her essay “Jackie Chan and the Black Connection,” which is included in Keyframes: Popular Cinema and Cultural Studies (Routledge, $90), Ithaca College associate professor Gina Marchetti explains, “Hong Kong provided a cheap product in the form of dubbed martial arts films to inner city cinemas trying to cut costs and develop a new clientele as television and the suburbanization of America eroded the downtown white or racially mixed audience of an earlier generation. …As inner city theaters closed, the African-American audience moved to Chinatown cinemas and, as these closed, the audience continued to rent or purchase legal and pirated Hong Kong martial arts fare on videocassette.”

Lennix adds, “Without a question, Bruce Lee was the uncontested idol for a lot of little black boys growing up in the ’70s. We absolutely accepted him as Soul Brother No. 1.”

| “Rush Hour” (1998) Jackie Chan, Chris Tucker Opening weekend: $33 million Opened at No. 1 Domestic box office gross: $104.2 million |

“The Matrix” (1999) Keanu Reeves, Laurence Fishburne Opening weekend: $27.8 million Opened at No. 1 Domestic box office gross: $171.4 million |

“Romeo Must Die” (2000) Jet Li, Aaliyah, DMX Opening weekend: $18 million Domestic box office gross: $56 million |

“Rush Hour 2” (2001) Jackie Chan, Chris Tucker Opening weekend: $67.4 million Opened at No. 1 Domestic box office gross: $226.2 million |

“Exit Wounds” (2001) Steven Seagal, DMX Opening weekend: $18.5 million Opened at No. 1 Domestic box office gross: $51.8 million |